The Goldilocks Zone

Using Race in Redistricting

The recent Supreme Court decisions concerning race and redistricting in Wisconsin and Alabama have made a lot of people very unhappy. Could the Court be laying the groundwork for further limiting or even striking down the Voting Rights Act entirely? If history is any guide, the answer certainly appears to be “yes.”

On Wednesday, the U.S. Supreme Court, in an unsigned per curiam opinion from which only Justices Sotomayor and Kagan publicly dissented, reversed a decision by the Wisconsin Supreme Court that had imposed a new set of state assembly and senate district boundaries to be used for the 2022 elections. This, after the GOP-controlled state legislature and the Democratic Governor, Tony Evers, had deadlocked on passing new maps, with Evers vetoing the heavily gerrymandered proposal that had passed the legislature. The Court’s reasoning, such as it is, was that the decision to adopt a plan that created an additional majority-minority district in the Milwaukee area misapplied the Court’s racial gerrymandering and Voting Rights Act precedents, by failing to conduct the proper inquiry necessary to determine whether such a district was necessary.

This confusing justification has already been met with a great deal of criticism from election law experts, and seems to fly in the face of a February decision in which a set of congressional district boundaries in Alabama were allowed to go into effect despite a lower court ruling that they violated Section 2 of the VRA. That both cases reached results favorable to Republicans has also further stoked the perception that the Court is engaging in a results-oriented jurisprudence when it comes to the most recent round of redistricting cases.

But the most interesting, and troubling, aspect of these decisions is that they represent an escalation of the decades-long effort by the Court to shift the Overton Window when it comes to the use of race in redistricting. By systematically narrowing the allowed use of race in crafting majority-minority districts under precedents like Shaw and its progeny, while simultaneously watering down the VRA provisions that require states to draw districts in which minority candidates have a realistic chance of electoral success, the Court has been subtly yet persistently undermining the dramatic expansion in minority officeholding that resulted from the Reagan-era amendments to the VRA in 1982. That process is now almost complete.

In my forthcoming book on gerrymandering, ONE PERSON, ONE VOTE, I borrow a term from our friends in astrobiology to illustrate how the VRA and the Equal Protection Clause intersect in the context of redistricting – The Goldilocks Zone. Put simply, race must be taken into account by states when redrawing districts in order to comply with the VRA, but not too much, or else the Fourteenth Amendment will be violated. Under Shaw, race cannot be the “sole” or “predominant” motivating factor behind the drawing of a district, nor, under Gingles, can it be ignored entirely. But somewhere along the continuum of colorblindness is a level of racial motivation that’s just right.

To understand how we got here, we need to know the basic history of the court’s jurisprudence on the use of race in redistricting (for much more detail on this – see my book). It’s time to dive, as Felix Frankfurter cautioned against in a famous 1946 opinion, into the political thicket.

In the 1960s, in a series of cases beginning with Baker v. Carr in 1962 and concluding with Avery v. Midland County in 1968, the Court recognized the principle of “one person, one vote” and extended it to apply to legislative districts at all levels of federal, state, and local government. States would now have to draw districts so that their populations were approximately equal, a reversal of the widespread malapportionment that had been present in prior decades. Around the same time, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 outlawed any denial or abridgement of the right to vote on account of race, and imposed stringent preclearance requirements on states that had previously engaged in discrimination.

No longer able to practice the systematic disenfranchisement of African American voters, states began engaging instead in a technique known as racial vote dilution, whereby minority communities were repeatedly drawn into districts with white majorities, preventing them from being able to elect representatives of their choice. After the Supreme Court failed to effectively address the problem of racial vote dilution in its 1980 Mobile v. Bolden decision, upholding a system that had seen blacks systematically excluded from the Mobile city council for the entire 20th Century, Congress passed the 1982 Amendments to the VRA, which allowed for instances of racial vote dilution to be invalidated based solely on their effects, without the need for plaintiffs to prove discriminatory intent.

In applying and interpreting these amendments in the 1986 case of Thornburg v. Gingles, the Court set the boundary of one end of the Goldilocks Zone. In circumstances where a sufficiently large, politically cohesive, and geographically compact racial minority group was being denied the opportunity to elect candidates of its choice due to racially polarized voting, states were required to draw majority-minority districts to avoid violating the VRA. The results were dramatic. The number of black elected officials in the United States went from 1,500 in 1970 to 8,000 in 2000. The number of Hispanic and Latino elected officials doubled between 1984 and 2014. With the encouragement of the Justice Departments of both George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton, states aggressively drew majority-minority districts during the 1990s. Then the Supreme Court decided that it was too much.

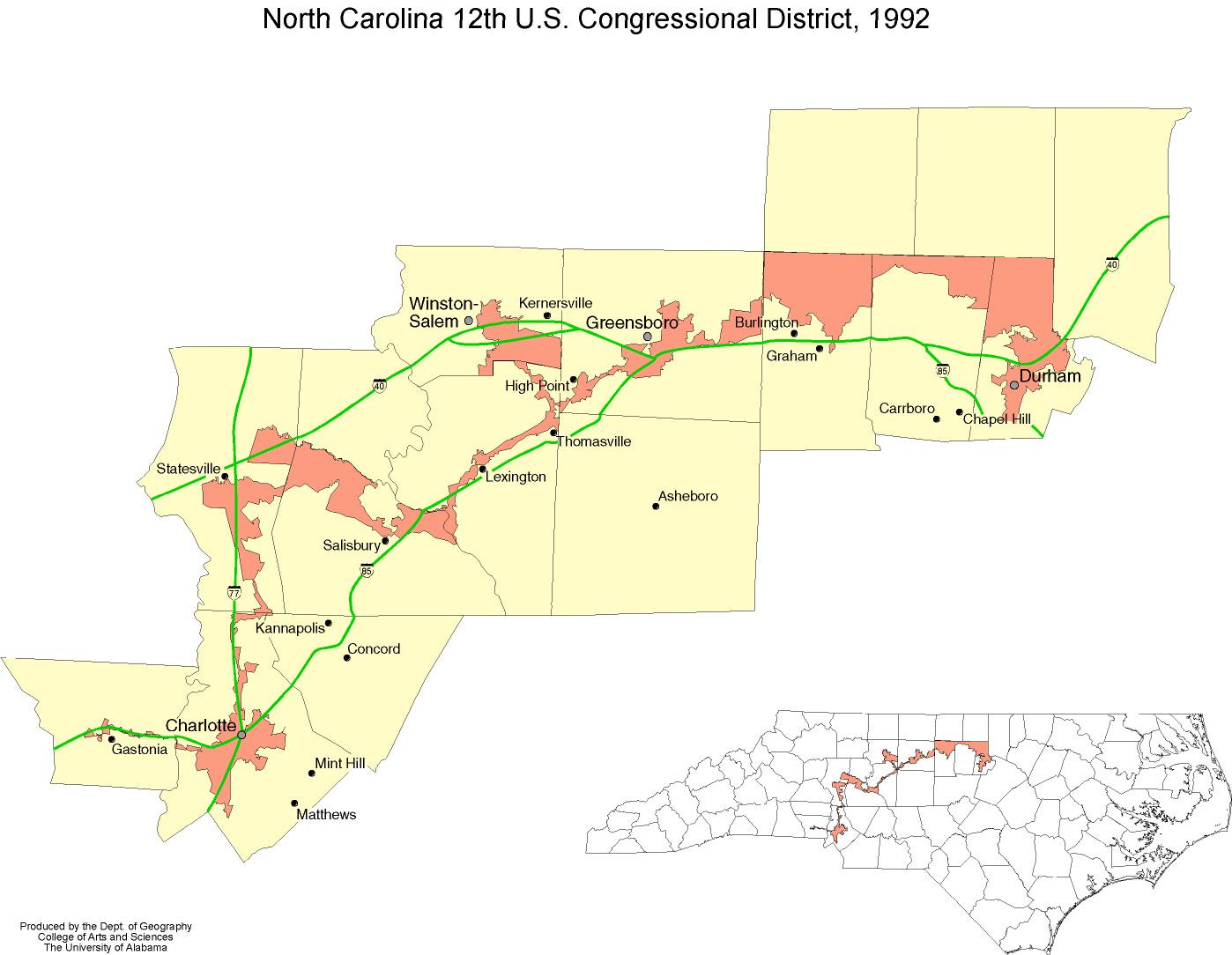

Beginning with Shaw v. Reno in 1993, the justices started applying strict scrutiny to the majority-minority districts that were being drawn by states. Taking particular ire at misshapen congressional seats like the North Carolina 12th and the Florida 3rd, they held that majority-minority districts must be narrowly tailored and use the least restrictive means of furthering the compelling interest of compliance with the VRA. This then established the other end of the Goldilocks Zone, where the use of race to craft a district becomes so pervasive as to violate the Equal Protection Clause. But it was never entirely clear where exactly the line was, or how far a state would need to push the use of race in redistricting to cross it. This lack of consistency was repeatedly flagged by Justice John Paul Stevens in his dissents from the 1990s racial gerrymandering rulings.

In the cases decided since then, the Court’s jurisprudence has been no less confusing, but two parallel trends have emerged. As their ideological median has shifted towards the conservative end of the political spectrum, the justices have systematically lowered the floor of how much race must be taken into account to comply with the VRA, while simultaneously lowering the ceiling of how much racial motivation is permitted under the Equal Protection Clause. The Goldilocks Zone has not only shrunk, but it has also clearly moved, in a direction that makes it considerably more difficult for states to represent the interests of minority constituents in redistricting.

In Johnson v. DeGrandy (1994), the Court determined that states do not have to maximize the number of districts in which minority voters can elect candidates of their choice to comply with Section 2. And in Bartlett v. Strickland (2009), they held that such a group must represent a numerical majority of the voting-age population for such a district to be necessary. Then, in the infamous 2013 case of Shelby County v. Holder, the Court took aim at the other pillar of the Voting Rights Act, the Section 5 preclearance requirements. By striking down the coverage formula in Section 4, the decision rendered the preclearance process inoperative, and legislation introduced before Congress to craft a new formula has repeatedly stalled. In the minds of a majority of the justices, aggressive legal enforcement of the voting rights of minority citizens is no longer necessary. “Nearly 50 years later,” John Roberts helpfully reminded us, “things have changed dramatically.”

But have they? The dismantling of the Voting Rights Act has picked up further steam in recent years, even as lower courts have continued to find that states are engaging in discrimination on the basis of race in the administration of their elections. In the 2018 case of Abbott v. Perez, to save a racially discriminatory Texas redistricting plan that had been struck down by the lower courts, the justices concocted a presumption of good faith racial innocence in cases where intent-based Section 2 challenges are raised. And in Brnovich v. DNC (2021), they manufactured out of whole cloth still further limits on the VRA’s applicability, with Justice Alito’s opinion outlining a series of fictional and entirely atextual “guideposts” for resolving Section 2 challenges to the time, place, or manner of casting ballots.

In the recent Alabama ruling, the Court ignored a meticulous and well-reasoned decision by a federal three-judge panel holding that Alabama’s decision to draw only a single district where an African American candidate stood a chance of getting elected – granting them 14% of congressional representation in a state where African Americans make up 27% of the population – constituted illegal vote dilution under the VRA. Their decision to stay the lower court decision was based on the dubious and highly amorphous Purcell Principle, which holds that federal courts should not ordinarily step in to change the rules immediately before an election takes place. If you’re wondering why the same principle shouldn’t also apply in the Wisconsin case, where the Court threw out a redistricting plan drawn with the intention of complying with the VRA at an even later point in the electoral cycle, well, those rules apparently only apply to the lower courts. As is the case with the federal judicial ethics code, the justices themselves appear to be exempt.

Might we be about to see another decision similar to Brnovich, further limiting the ability of plaintiffs to bring challenges to racial vote dilution in redistricting based on invented guideposts found nowhere in the actual text of the VRA? Could the Court even be laying the groundwork for a ruling striking down the 1982 Amendments to the VRA entirely? The recent twin decisions in Alabama and Wisconsin certainly suggest that such a reckoning may indeed be on the cards.