Snatching Defeat from the Jaws of Victory

How Democrats Lost Redistricting

After trailing in both polls and prediction models for most of the year, Democrats came within a whisker of retaining their House majority in the midterm elections. And while they ultimately fell short, the red tsunami that most pundits and prognosticators had predicted did not materialize. But a closely contested election for Congress was never likely to have been decided by the voters in November. Instead, it was decided during a hectic 30-day period in March 2022, when everything that could have gone wrong for the party in the drawing of districts did go wrong.

At the beginning of the year, Democrats had been poised for their most successful national redistricting effort since the 1980s. Amid rising inflation, anemic approval ratings for President Biden, and a stalled legislative agenda on the Hill, they fought back at the state level against the gerrymandered House maps that were the legacy of the GOP’s highly successful REDMAP redistricting effort following the 2010 census.

They seemed well-positioned to claw their way back to national parity, or even outright advantage, as the electoral playing field took shape. Commentators observed that while the new House maps would most likely not be enough to save them from the expected red wave in 2022, they would place the party on a solid national footing for the rest of the 2020s, a lone bright spot amid a deluge of negative news cycles.

Much changed between then and November. The Supreme Court’s decision overturning Roe v. Wade energized the Democratic base, sparking huge turnout in primary elections, including in Kansas, where voters rejected an anti-abortion ballot measure by a 59-41 margin. Republicans nominated a slew of inexperienced and less electable candidates in major races, torpedoing their odds of regaining the Senate. The party consistently overperformed Biden’s 2020 margin in each of the special elections held after the Dobbs decision, including upset victories in Republican-leaning seats in Alaska and New York.

None of these were enough to carry them across the finish line in the midterms. Instead, their undoing was a product of the same electoral skullduggery and subversion of democracy that had provided their silver lining earlier in the year: gerrymandering. When factoring in their own redistricting setbacks in blue states, GOP successes in red ones, and a series of adverse state and federal court decisions, gerrymandering was a key reason why they lost control of the House. The redistricting cycle giveth, and the redistricting cycle taketh away.

The march madness began in Ohio. Despite a state supreme court ruling that had struck down the gerrymandered House map drawn by the GOP-controlled state legislature, the bipartisan-in-name-only Ohio Redistricting Commission nevertheless imposed another plan on March 2 with an equally large Republican bias. While the court then struck it down a second time in July, that ruling came too late, allowing the gerrymandered districts to be used for the 2022 elections. 9 of Ohio’s 14 Representatives in the 118th Congress are Republicans elected from unconstitutional districts, because the state GOP was able to successfully run out the clock.

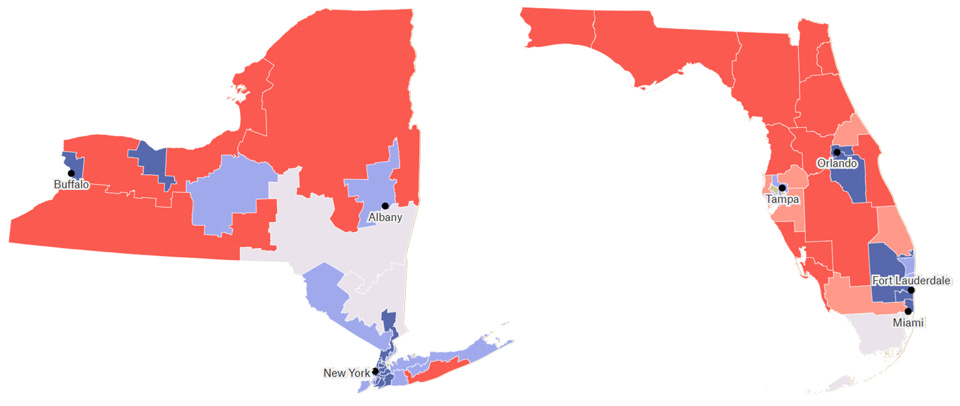

Later in the month, more dominoes fell, and this time it was blue state judges who were dealing the blows. In Maryland, a state court struck down the Democratic legislature’s House plan, passed over the veto of GOP governor Larry Hogan, that had guaranteed the party 7 of the 8 congressional seats in the upcoming election. Then, in New York, a judge also overturned the outrageous 22-4 Democratic gerrymander that had been the shining jewel of their sudden resurgence in the redistricting wars. And while judges appeared eager to police Democrats’ gerrymandering excesses in blue states, the same could not be said about red ones.

The Kansas Supreme Court, despite a 5-2 majority of Democratic appointees, allowed the Republican gerrymander of that state’s House districts to stand. Additional decisions in Voting Rights Act challenges to districts Alabama and Louisiana, where the Supreme Court allowed maps to be used that lower federal courts had deemed illegal, moved two more seats from the blue to red column. GOP gerrymanders in Utah, Tennessee, Georgia, and Texas tipped the scales even further, moving the median House seat from something resembling parity to one favoring Republicans by 2.5%. Democratic gerrymandering successes in Illinois and New Mexico offset some of these gains, but whatever early redistricting momentum they had built had now evaporated.

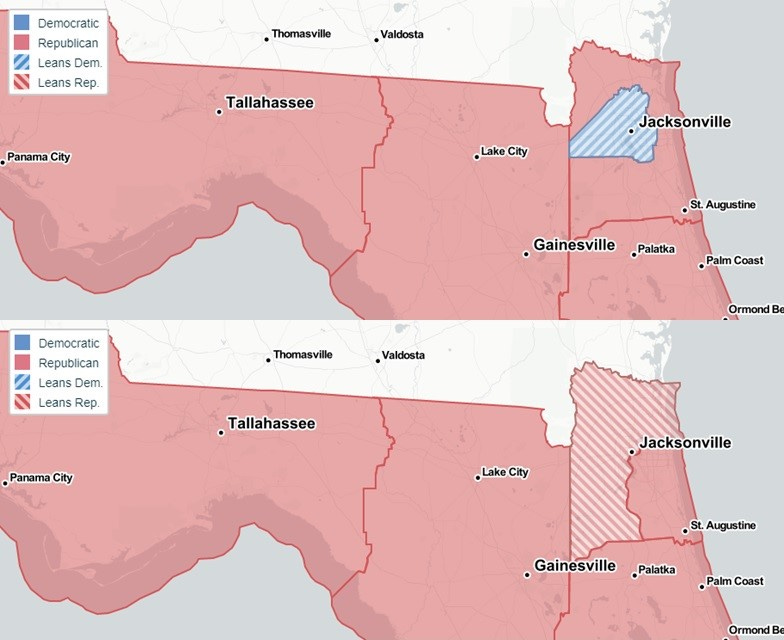

The final nail in the coffin of the Democratic redistricting agenda came from one of their most hated villains: Florida Governor Ron DeSantis. On the last day of March, he took the unprecedented step of vetoing a congressional redistricting plan passed by a legislature controlled by his own party. DeSantis then browbeat the Florida GOP into rubberstamping a heavily gerrymandered map of his own design. While the equally egregious Democratic gerrymander in New York was struck down, the state courts in Florida inexplicably allowed the DeSantimander to stand, ignoring a provision in the state constitution that explicitly outlaws partisan gerrymandering.

In the space of a month, enough seats had flipped from blue to red to be decisive in a close election, all without a single vote being cast. And while incumbent retirements, rising gas prices and continuing inflation, and the general tendency of the president’s party to lose seats in midterm years may have shifted some momentum in the Republican direction down the stretch, gerrymandering remains the key reason why even when Democrats are winning, they’re still losing.

Lack of responsiveness to the will of the people is the inevitable effect of our broken redistricting system. Legislation to outlaw partisan gerrymandering of House districts has repeatedly failed in Congress, and despite some progress at the state level, control of our democratic institutions remains at the whim of whichever side happens to finagle the better maps. “Redistricting is like an election in reverse!” the late GOP gerrymandering guru Thomas Hofeller once quipped during an interview on C-SPAN. “Usually the voters get to pick the politicians. In redistricting, the politicians get to pick the voters!”