It’s perhaps a little hyperbolic to say that the state of Wisconsin is no longer, in any meaningful sense, a democracy. But not by much. The state’s governor, at least, is still an elected position accountable and responsive to the will of the people, but the state legislature is not. It hasn’t been for more than a decade.

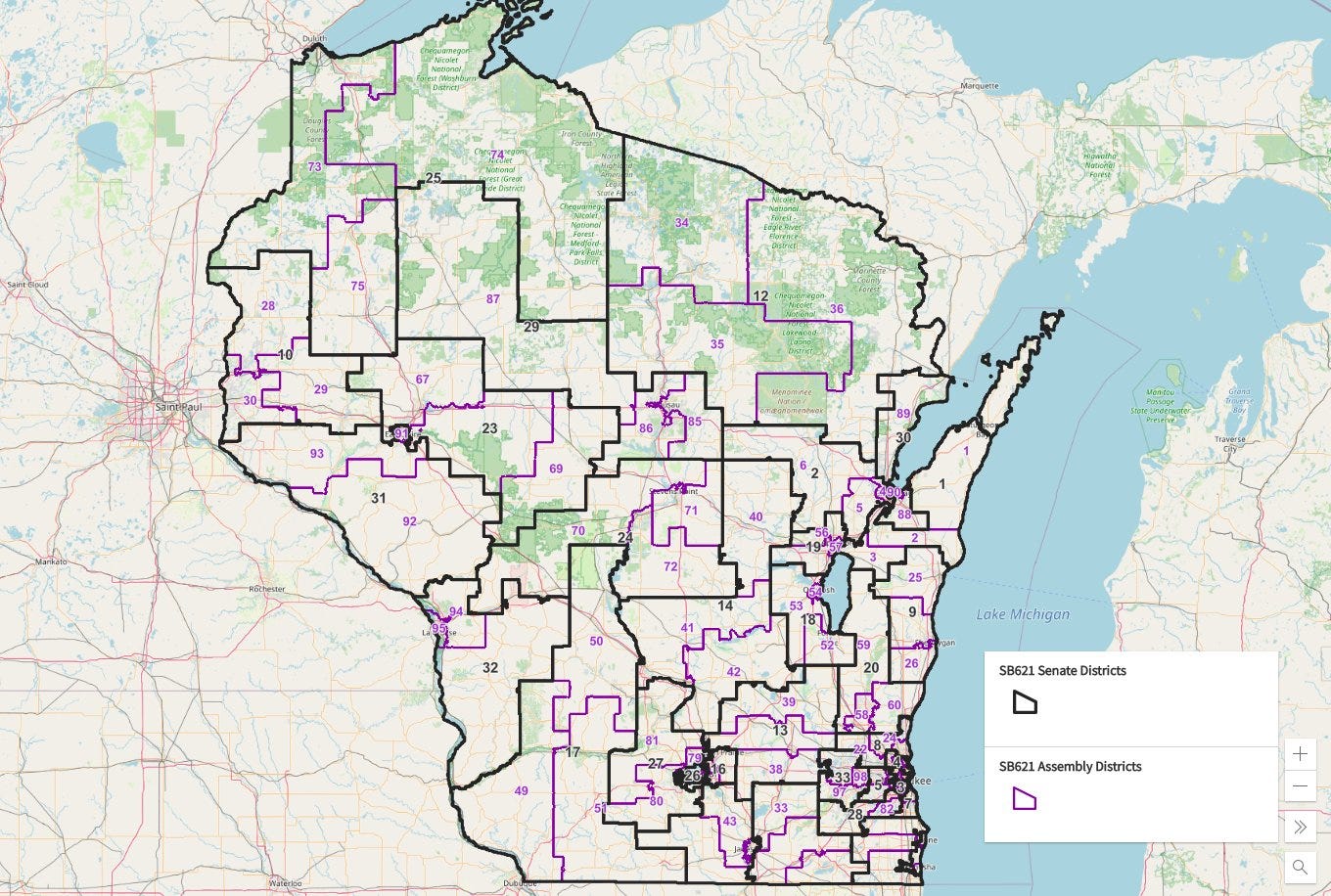

Late last week, the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled 4-3 along ideological lines (judge Hagedorn, who was elected with GOP support but has been something of a wild card in recent redistricting cases, joined the court’s conservative bloc in majority with the three liberals in dissent), to impose Republican-drawn maps for the state Assembly and Senate that will remain in place for the remainder of the decade. These maps are extraordinarily biased towards the GOP, which has commanded majorities in both state legislative chambers since the gerrymander that was put in place in 2011 during Scott Walker’s tenure as governor.

It’s not unusual for maps drawn by supposedly neutral arbiters to contain mild or even moderate levels of partisan bias. The California Citizens Redistricting Commission, for example, which drew extremely fair maps for both congress and the state legislature a decade ago, this time around unveiled plans that are significantly more favorable for Democrats. And this same Wisconsin court, just a few weeks ago, also imposed a U.S. House map that, though submitted by the state’s Democratic Governor, Tony Evers, adopted a least-change approach that skewed heavily in favor of the GOP.

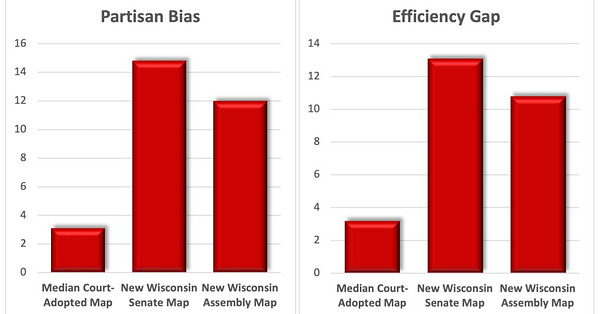

But commission and court-drawn redistricting plans tend to be, on average, significantly fairer than those drawn by the politicians themselves. An analysis by Rob Yablon, a professor at the University of Wisconsin Law School, found that since 2000, the more than 20 state legislative plans adopted by courts, usually in situations when, as happened in Wisconsin, divided government causes the legislature and the governor to deadlock on passing a new map, had a median efficiency gap of 3.2 and a median partisan bias of 3.1, with the vast majority falling within one standard deviation of partisan parity.

This is not unexpected. Courts, unlike politicians for whom the perverse incentives of partisan gerrymandering can be too tempting to resist, are supposed to conduct redistricting in a nonpartisan and neutral fashion in accordance with the requirements of state and federal law, and such an approach usually yields results that are at least within shouting distance of fairness.

I found similar results in my 2017 book, Drawing the Lines, in which I analyzed all congressional plans that were in place for elections between 1990 and 2010. There, I found a significant increase in partisan bias in both district vote share and probability of victory when redistricting was controlled by one political party as compared to an independent commission or the courts. I also found that judicial redistricting in particular tended to produce maps that were more competitive and responsive than any of the alternative approaches.

The Wisconsin Supreme Court’s ruling, however, adopted maps with efficiency gaps of R+10.8 (Assembly) and R+13.1 (Senate), and partisan bias metrics of R+12.0 (Assembly) and R+14.8 (Senate), making them by far the most gerrymandered state legislative plans to be adopted by a court in the last two decades. And even more unusually, the court declined to either hire a special master to draw its own map based on neutral redistricting criteria, or adopt one of the fairer alternatives proposed by the litigants themselves, instead imposing without modification the plan that the GOP legislature had drawn.

This kind of overt partisan gerrymandering by the judicial branch is rare, but it’s not unprecedented. In fact, something extremely similar happened in Texas two decades ago, only on that occasion, it was the Democrats who were the beneficiaries.

Perhaps the best political science book that’s been written on the political realignment of the American South since the Civil Rights Movement is Earl and Merle Black’s 2003 tome The Rise of Southern Republicans. In it, they document the secular electoral realignment that has seen conservative white southerners, who formed the cornerstone of the New Deal coalition that allowed the Democratic Party to maintain its stranglehold on southern politics, and control of Congress, for most of the 20th Century, gradually defect to the GOP.

While the presidential candidacy of George Wallace in 1968 drove a permanent wedge between conservative southern Democrats and the party’s more liberal northern faction, it took several decades for that transformation to fully manifest itself, particularly at the state and local level. By the time of the 1992 redistricting cycle, Democrats still controlled the levers of power in places like Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Tennessee, Texas, and West Virginia, and they attempted to use their control of the redistricting process to stave off the rising Red Tide.

Most of the gerrymanders that the Democratic Party attempted in the South during the 1990s were unsuccessful. Political scientists Bernie Grofman and Tom Brunell nicknamed the plans “dummymanders,” because many of them sliced their margins too thin, creating competitive seats that flipped to the GOP in the 1994 wave election. One notable exception was Texas.

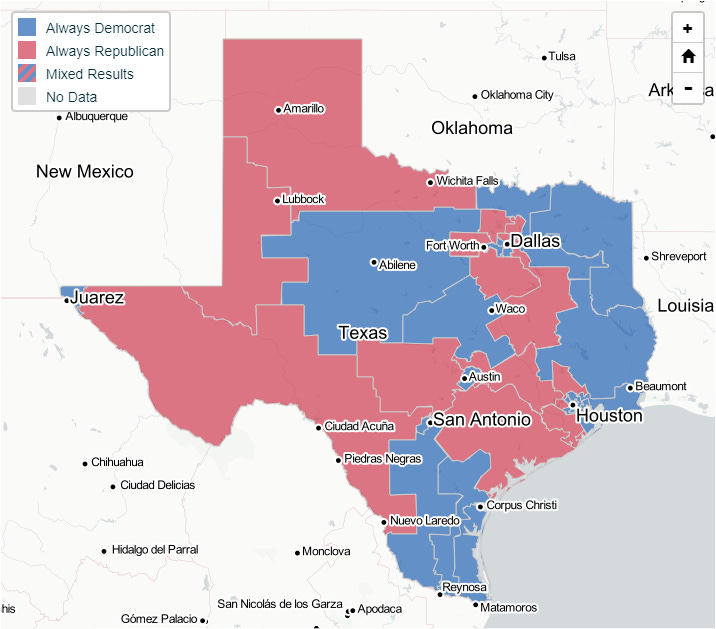

In the Lone Star state, despite dwindling popular support, Democrats were able to keep control of a 78-72 majority in the state house and a 17-13 edge in congressional seats through the 2000 Census, despite winning only 47% of the statewide legislative vote in the 2000 election. The governorship, however, had flipped Republican in 1994 with the election of George W. Bush, as did the state senate later in the decade, by a narrow 16-15 margin, meaning that Texas, like Wisconsin in 2021, would have divided government for the 2001 redistricting.

When the legislature was unable to agree on a congressional redistricting map, and the Texas Supreme Court overturned a lower state court ruling that attempted to impose its own plan, the question was punted to a special three-judge federal district court panel consisting of two Clinton appointees and one Reagan appointee. And faced with the unenviable job of attempting to craft a redistricting plan that added two new growth seats to the landscape without any guidance from the elected branches of the state government or the state courts, they opted for a map that protected incumbents, preserved the cores of prior districts, and largely maintained the existing Democratic gerrymander.

In the 2002 election, the Democrats held on to control of the 17 seats that they had held before redistricting, while the GOP picked up the two growth seats, bringing them from 13 to 15. The court-imposed plan, which had an efficiency gap of D+11.8, remarkably similar to the pro-GOP bias evident in the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s map, was sufficient to allow the Democrats to capture a 17-15 majority in congressional seats with just 44% of the popular vote.

But there are a couple of key differences between the two cases, differences that tend to cast the federal judges in Texas in a somewhat more favorable light than those on the Wisconsin Supreme Court. Unlike in Wisconsin, the federal three-judge panel did appoint a neutral special master to assist in the redrawing of the districts. They also documented in their unanimous opinion how they attempted to draw a plan using “neutral districting factors” wherever possible, including compactness, contiguity, and respecting county and municipal boundaries.

Their descriptions of the process of drawing the map come across as a naïve, albeit good-faith attempt to produce a least-change map that corrected some of the more egregious contortions of the earlier Democratic gerrymander, avoided pairing or unseating incumbents, and protected racial minorities. But their choice of a starting point for the map, locating the two growth seats in heavily red suburbs of Dallas and Houston, had the effect of pushing all of their subsequent decisions in the direction of the creation of a pro-Democratic bias elsewhere in the state.

The Wisconsin Supreme Court made no such effort to craft a fair plan. They adopted, without modification, the heavily gerrymandered Republican districts that had been passed by the legislature, while rejecting four other proposals that would have produced a more equitable result. These included an algorithm-drawn map that the court conceded “perform[ed] well on several race-neutral criteria,” but deemed “constitutionally flawed” because it included race as one of its input variables.

There are likely to be more of these types of rulings to come. As I explained in my prior post on The Goldilocks Zone, the shifting of the Overton Window with regard to the use of race in redistricting, as reflected in the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to overturn the state legislative maps drawn by Governor Tony Evers, makes it next to impossible for states to properly represent the interests of minority constituents in redistricting without running the risk of the courts declaring that it violates the Constitution.

We’re rapidly approaching a future where any consideration of race in the drawing of districts is prohibited, leaving Republican states free to gerrymander seats held by Black and Latino politicians into oblivion, while tying the hands of Democrats who desire to protect minority representation. It’s happened in Wisconsin, it’s happening right now in Florida, and it will soon be coming to a state near you.