Foxes Guarding Henhouses

How Gerrymandering Undermines State and Local Democracy

The St. Johns river bifurcates the city of Jacksonville, Florida, one of the most politically competitive large municipalities in America. Jacksonville has supported Republicans and Democrats in elections for Mayor, Governor, and President since 2018.

Both the city and the river have also become ground zero for controversies over gerrymandering, the deliberate manipulation of district boundaries to influence the results of elections. Despite its status as a swing city in a swing state, both of Jacksonville’s congressional seats are held by Republicans who won by large margins in the 2022 midterms, and its city council has a 14-5 GOP majority.

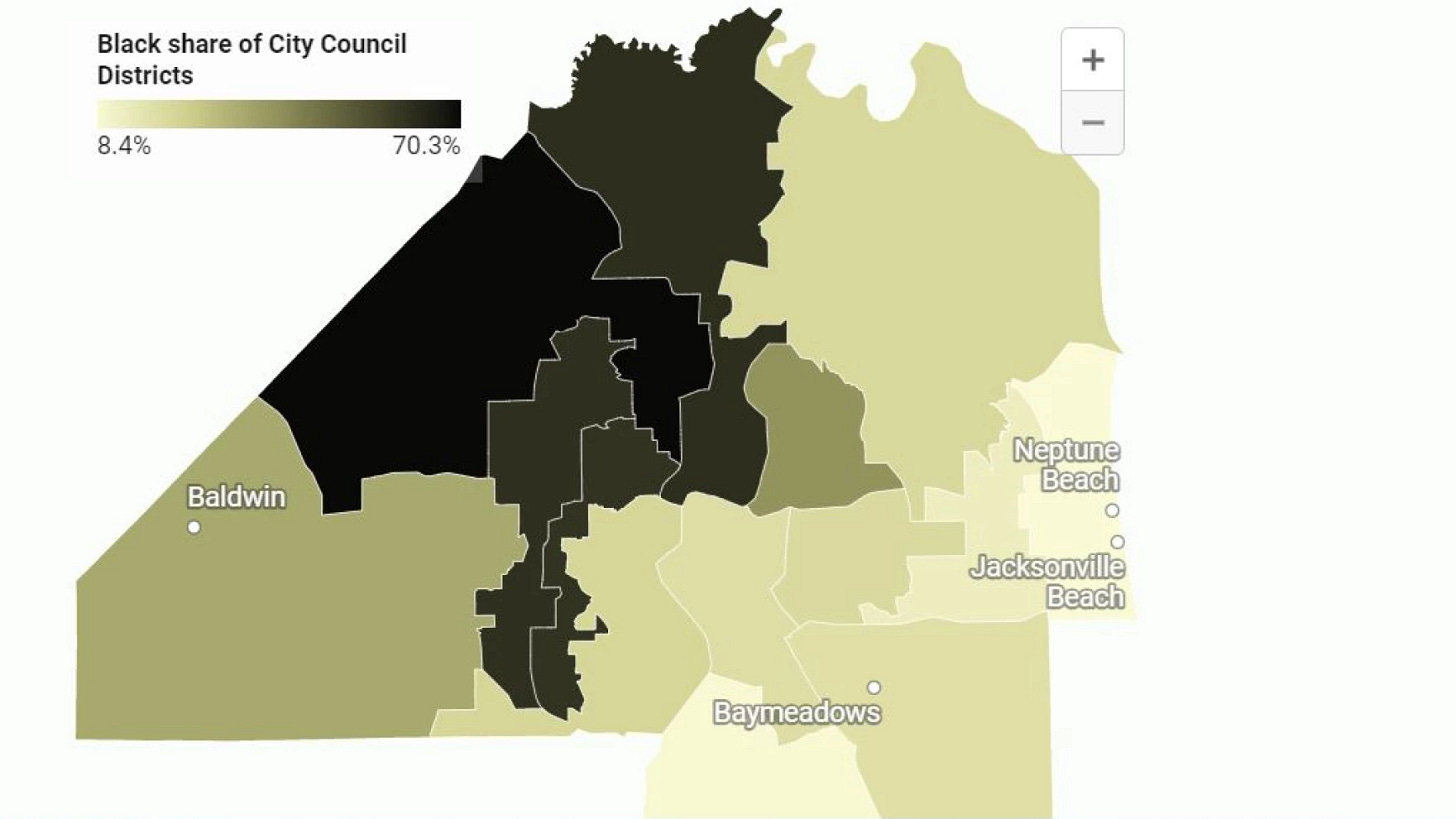

Jacksonville’s districts are Republican by design. Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, who seized control of the redistricting process from the state legislature after the 2020 Census, intentionally split the city along the river into two House districts, cracking its Democratic urban constituencies and diluting their votes with large infusions of rural Republican voters. The city council packed Black Democrats into four supermajority seats, leaving enough Republicans in surrounding areas to ensure that the GOP majority remains in power, a move that a federal court determined to be unconstitutional racial gerrymandering.

Under the constitutional principle of “one person, one vote,” every state must redraw its electoral districts at all levels of government after each Census to ensure that political power and influence are divided equally among the populace. The results of the 2022 elections indicate the stark divide between states that allow elected politicians to control the redistricting process, and those that have created independent nonpartisan commissions to perform that role.

Democrats fought their way to a draw in the midterms, maintaining a narrow majority in the Senate while conceding an equally slim advantage to the GOP in the House. But in many competitive states state legislative majorities remain far out of reach, largely because of the influence of gerrymandering.

Among the closest swing states in the 2020 presidential election were Georgia, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Michigan on the Democratic side, and North Carolina, Florida, Texas, and Ohio in the GOP column. All eight were heavily gerrymandered by Republicans after the 2010 Census, where the majorities that swept into power during the Tea Party wave quickly set about entrenching their institutional control.

In those eight swing states, Democrats had won a majority of seats in at least one state legislative chamber in 40% of the elections held from 2000-2010. After gerrymandering, from 2010-2020 that number became 0%. In this group of politically competitive states, where more than a third of Americans reside, a single party had unfettered control over the legislative and policy agenda for an entire decade.

The result was legislation considerably out of step with the preferences of the populace. On issues like abortion, gun control, and Medicaid expansion, the legislatures of these states have consistently pursued an agenda that polls suggest is broadly unpopular with the voters who elected them. When incumbent legislators know that both their own seats and their party’s majority is safe no matter how the people vote, they become emboldened to pursue insular policy goals that only please their party’s base.

Witness the recent flurry of restrictive abortion statutes enacted by GOP-controlled states in anticipation of and reaction to the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson. Then compare these with the results of 2022 ballot initiatives relating to abortion rights in Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, and Montana, hardly bastions of progressivism. In all of these, the pro-choice position has prevailed, even as state legislatures have been pushing ever more draconian abortion bans.

The contrasting midterm results in Michigan and Wisconsin, two demographically and politically similar Midwestern states, illustrate both the destruction that gerrymandering can wreak on democratic apparatus of a state if left unchecked, and how effective the best practices in redistricting reform can be at combating it.

In Wisconsin, where the GOP legislature once again controlled redistricting, Democratic Governor Tony Evers won reelection by a close but comfortable margin, while incumbent Republican Senator Ron Johnson narrowly defeated Democratic challenger Mandela Barnes. Despite this, Republicans won large majorities in both state legislative chambers, eventually reaching the two thirds supermajority threshold that will allow them to override an Evers veto along party lines.

But in Michigan, where the newly established citizens redistricting commission drew fair maps for both the state legislature and Congress, the coattails of Gretchen Whitmer were sufficient to pull enough down-ticket Democrats over the finish line. They took control of both chambers of the state legislature, the first time the party will have held a trifecta in the state in 38 years.

Partisan gerrymandering works by systematically cracking and packing blocs of voters from the targeted party. Cracking disperses them among multiple districts where their influence is spread out, and they are unable to vote in large enough numbers to win any of the individual races. Packing concentrates them into districts where they vote in numbers far greater than necessary to achieve victory, wasting votes that now cannot contribute to majorities in other places. By combining these tactics, the majority party creates a map where the minority party’s voters are arranged as inefficiently as possible, preventing their voting power from translating into legislative seats.

Six of Wisconsin’s eight congressional seats voted Republican, with Democrats averaging 73% of the vote in districts they carried and Republicans 61%. This discrepancy demonstrates that Democratic voters were deliberately packed into supermajority districts to dilute their votes, allowing Republican candidates to win surrounding seats by smaller margins. In Michigan, neutral maps produced a 7-6 Democratic edge in House races, with Democrats averaging 61% and Republicans averaging 59%, indicating no evidence of systematic partisan bias.

In other words, the heavily partisan redistricting process in Wisconsin has created another decade of biased election results and gerrymandered districts, while the independent citizen-led process in Michigan produced fair maps where the votes of the people will determine who gets to govern the state.

The results of the midterms show that the most effective antidote to gerrymandered state legislative majorities is to reform the process itself. To remove the legislature from the district-drawing equation, neutering the incentives that lead incumbent politicians to prioritize preserving their own jobs, and the majorities they command, over effective democratic representation.

The blueprint for how to gerrymander a party into permanent legislative control was drawn by the late Republican redistricting guru Thomas Hofeller, one of the most influential political operatives of the last 50 years. He realized that by diligently building up majorities in state legislative chambers, the party would not only empower itself to implement its policy agenda at the state level, but also maintain a considerable edge in the battle for control of Congress.

In both 2012 and 2022, the GOP only won a majority of the U.S. House seats because of its successful gerrymandering ground game. Democratic gerrymandering has, at least recently, been confined to already heavily blue states like Illinois, Maryland, and New York. And while no less offensive to the norms of democratic accountability and responsiveness, it has produced less return on investment in terms of substantive influence on government policy.

New Mexico stands as one of the few examples of a swing state where Democrats have been able to successfully implement the Hofeller playbook, to the detriment of its Republican voters. Despite averaging less than 55% of the popular vote, Democrats won all three of New Mexico’s House seats in the 2022 elections.

In the 1970s and 80s, however, gerrymandering was an effective tool for racist Southern Democrats seeking to suppress the Black vote, and their more liberal counterparts in California to resist the Reagan electoral wave.

Extreme gerrymandering can sometimes be combated by lawsuits, though litigation remains an expensive and time-consuming vehicle for change, and since the Supreme Court’s 2019 ruling in Rucho v. Common Cause it is only an option in state courts. But such suits did lead to the dismantling of Democratic gerrymanders in New York and Maryland, and Republican gerrymanders in Pennsylvania and North Carolina following the 2020 Census, although a switch in partisan control of the North Carolina Supreme Court later led to that decision being reversed.

The history of gerrymandering in America suggests that it is an inevitable phenomenon that emerges wherever those with strong political incentives have the authority to draw the lines in district-based electoral systems. Independent commissions eventually became the norm in almost every other representative democracy, but the decentralization of election administration in the United States has proved a major hurdle to implementing reform.

The 2022 midterms mark the beginning of a new era in American gerrymandering, where technology and data allow politicians to consign their opponents to permanent minority status, pack state courts with sympathetic judges, and resist any effort to impose fair maps.

This disturbing decline of democracy in American statehouses and city halls comes at a time when legislatures are considering ever more restrictive voting laws, and candidates pushing the false narrative of widespread election fraud are winning races at all levels of government. The creation of safe seats and safe majorities through gerrymandering further robs the people of the power to hold those elected representatives accountable, particularly in the state and local races that have the most significant and direct effects on their lives.

As Wisconsin slides further into single-party rule by fiat while Michigan emerges into a new era of healthy and competitive democracy, the lesson is clear. Only independent redistricting can guard against democratic backsliding, and only the people themselves, through citizen-led commissions, can be trusted with upholding the fundamental principle of one person, one vote.

At the national level, Congress must pass legislation requiring commission-drawn districts to be used for all federal elections. And at the state level, redistricting must similarly be reformed to promote fairness in state and local elections.